The Art of Jenbe Drumming: The Mali Tradition Vol. 1

Three masters of traditional jenbe celebration drumming present the clear beauty and explosive power of their music. They are of the same stylistic tradition and musical descent; also they are playing the same jenbe drum and are accompanied by the same dunun player. Thus the enormous differences you hear between the players, for instance concerning sounds and playing style, are clearly comparable and directly correspond to differences in generational and personal styles. The complete transcriptions of all the pieces are available in The Jenbe Realbook Vol. 1, a book of music notation directly corresponding to this CD.

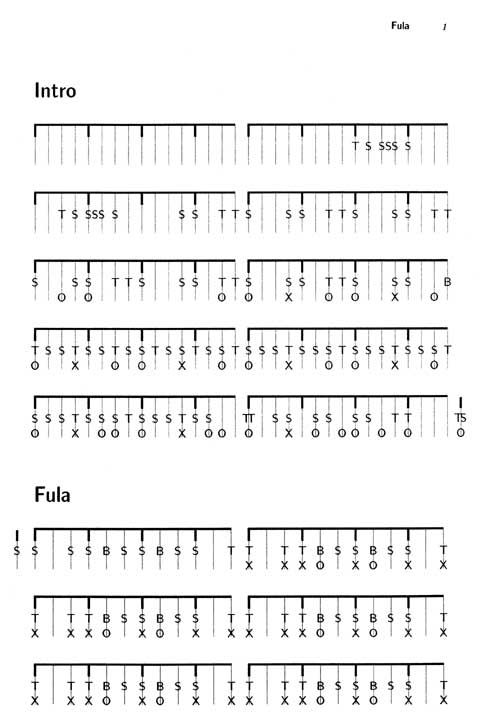

1. Intro + Fula 04:25

2. Madan 06:25

3. Maraka 04:44

4. Sogoninkun 04.43

5. Sabaro a, b, c 04:55

6. Woloso 04:20

7. Kòmò 06:50

8. Kòfili 05:37

9. Kirin 05:12

10. Burun 03:48

11. Maa Nyuman 01:44

12. Jina I 04:18

13. Jina II 02:52

14. Jina III 02:41

total playing time 63:04

Jenbe: Jaraba Jakite (Tracks # 1 – 5)

Yamadu Dunbia (Tracks # 6 – 10)

Jeli Madi Kuyate (Tracks # 11 – 14)

Dunun: Madu Jakite (all tracks)

Recorded 1995 in Bamako (Mali) by Rainer Polak * All titles: Traditional * Mix and Premaster: Tobias Ott and Rainer Polak * Liner notes: Rainer Polak *

you can easily download the CD worldwide via: http://www.amazon.com/Jenbe-Drumming-Mali-Tradition-Vol/dp/B000UR2ED4/ref=sr_f3_1ie=UTF8&s=dmusic&qid=1204151640&sr=103-1

The Art of Jenbe Drumming: The Mali Tradition Vol. 1

The recordings

Three masters of traditional jenbe dance drumming present the clear beauty and explosive power of their music. Of course the music of a jenbe dance celebration cannot be adequately documented because it represents part of a dynamic event which can only be fully grasped by witnessing all its interlocking elements. The sound recording of a celebration would lack the movement of the dancers and the whole atmosphere of colors, smells, and enthusiasm. The recordings presented on this CD, moreover, were made not in the context of a celebration at all, but in a school yard in the Badialan quarter of Bamako. The drummers performed for the microphone, without rehearsals, without arrangements, and without an underlying notion about how to convey celebration music without a celebration. It was the first time any of them had done a studio recording. They spontaneously created a kind of »art music« in a space without references, an abstract translation of music traditionally played for celebrations. The original live tracks were neither cut nor overdubbed.

Note that all three jenbe players were of the same stylistic tradtion and musical descent, and that they were playing the same jenbe druing during the recordings, and were accompanied by the same dunun player. And yet one hears enormous differences in sound and playing style; these correspond to differences in generational and personal styles.

you'd like to hear while reading along? www.myspace.com/bibiafricarecords

The ensemble

This CD presents masters of the jenbe in duet performances with an accompanying bass drummer – one jenbe, one dunun, no bells. Playing in this smallest version of a jenbe drum ensemble was typical for the celebration music style of Bamako in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Today, trio, quartet, and even larger ensembles are the rule, and many stylistic differences, from ballet music, the playing styles of Conakry and Abidjan, and even of the international jenbe scene based in the rich West, have come to change the Bamako style. Thus the recordings featured here represent sort of a classical aesthetic ideal of Malian jenbe music as crystallized in its capital Bamako after independence.

Only mature musicians can master duet playing and know how to create its typical fascinating musical density, balancing the tension between flow and transition, between communal groove and individual expressivity, between tradition and improvisation, between form and trance. The »challenge of the void« that duet playing presents to many holds no threat for the drummers of Baladian, because their playing is based on decades of experience as performers in this sort of ensemble. Fabulously sure of their instruments, guided by close communication even in the boldest passages, the void represents space they enjoy filling with sound.

The reduced line-up also has the advantage of very clear and transparent sonic reproduction. Thus the listener can not only perceive the fundamental musical structures, but also experience the high art of drumming, the »talking of the drum«, in its finest rhythmical nuances and timbral shades.

The musicians

Jaraba Jakite, born approx. in 1953, moved to Bamako in 1984. Since then his sensationally physical, dancing, drumming style rapidly earned him the reputation of a great »worker of the drum.« Jaraba, the »Great Lion«, used to be one of the most sought after celebration drummers of the city. After a successfull tour in Germany with Madu Jakite and Rainer Polak in 2000, his state of health got increasingly worse until he passed away early in 2005. Jaraba Jakite will enrapture the listener with his sharp and expressive playing on tracks 1-5.

Yamadu Bani Dunbia, born in approx. 1917 in west Mali, was recruited as young man by the French colonial army and fought in World War II as a conscripted soldier against the allies of the Germans in the Mediterranean. In the period after 1945, the celebration culture in Bamako and other Western African capitals began to flourish. Dressed up as new, it practically boomed in the 1960's, the early years of African independence. Returning from the war, Yamadu Dunbia found himself in the capital as an uprooted man.

Possessed by a spirit in his childhood, healed and called to be a drummer, he was one of the first and most successful professional drummers to take advantage of the propitious moment and make a trade of their art. 78 years young at the time of these recordings, he was still widely known as the legendary patron of the jenbe, whose playing was capable of calling the spirits so swiftly that people fall in a shaking trance in a matter of seconds. This pioneering Bamako jenbe player, who trained Jeli Madi Kuyate, Jaraba Jakite, Madu Jakite, Drissa Kone, and many, many others, passed away in 2002. Yamadu breathes life into the jenbe on tracks 6-10, where he makes the instrument sing, playing not a single beat too much, and placing each beat in superior style. Sometimes he is playing the jenbe so emphatically that he would spontaneously start to groan, shout or sing along with his own performance.

Jeli Madi Kuyate was born approx. in 1949 and came to Bamako from his native village to the south of the capital when he was 12 years old. A student of Yamadu Dunbia's, he was an early success and has toured many countries including France, China, Canada and Korea as a musician with the Ballet Nationa du Mali. His dexterous, elegant style of playing gives life to selections 11-14.

Madu Jakite, born approx. in 1960, is an expert on the kònkònin bass drum and accompanies the soloists on all the tracks.

Repertoire

Reflecting the diversity of Mali's various regions and peoples, these recordings represent facets of generations and styles. On the other hand, they also reflect the oneness of a jenbe tradition that is constantly being transformed in the melting pot of a multicultural capital.

1. Fula is the Malian name given to the Fulani (Fulbe, Peulh), a pastoral people indigenous in all of Western Africa. This rhythm goes back to the Fulbe of the interior delta, where the Niger River inundates an entire region during the rainy season. It was originally played on drums quite different from the jenbe, which goes to show how tradition changes—and survives.

2. The Madan is a Maninka dance from the Mande region situated to the south of Bamako; the Mande was the heartland of the medieval Malian empire. Many drummers in the capital, like Jaraba Jakite, come from this region and are very fond of this rhythm.

3. The Soninke from the north of Mali are a trading people called Maraka in the language of Bamako. The rhythm of the same name is a veritable standard at wedding celebrations in the capital, the most frequently played of all rhythms.

4. The Sogoninkun is a profane, acrobatic masked dance which was brought to the metropolis from the Wassoulou in the south-east of Mali, an area rich in musicians and hunters. Sogoninkun means »gazelle's head« and stands for the mask, the dance, and the rhythm.

5. Sabaro is the solo drum, a feast, and a rhythm of the Wolof from Senegal. People come to the metropolis from all parts of the country, even crossing state borders, as in this particular case. They bring their own cultural needs with them, while at the same time making their own contributions to culture. The broader the repertoire of the drummers, the larger is their potential audience. The drummers in the cities therefore adapt the rhythms of as many peoples and regions as possible. Of course, doing so is also fun.

6. Woloso is a dance of the descendants of »captives« or »slaves« who played an important role at the royal courts of the past and who held important positions.

7. The initiation feasts of the Kòmò secret society were accompanied by a rhythm of the same name. Only the initiated were allowed to see the Kòmò mask dance. Although this is a thing of the past in Bamako, the rhythm has survived and is still being handed down.

8. Kòfili is an old rhythm from the territory of the Bamana in central Mali. The Bamana are the largest Malian people, and their language is used in the capital, in the schools, and on the radio alongside French.

9. Kirin – spelled n’gri in some other publications – originates from the Wassoulou region, just like the rhythms presented in tracks 4 and 10. For this track, the venerable old master Dunbia has played a both sedate and daring rendition of the rhythm unequaled by the frenzied drum rolls of the up-and-coming junior jenbe players from Bamako.

10. Burun, the horn. Apart from old Dunbia, nobody in Bamako still recalls this rhythm, which was used to accompany the play of trumpets.

11. Some years ago, Maa Nyuman was popular with a group distinct from the celebration drummers—the theater and ballet drummers. These musicians attempt to capture the celebration culture in fixed arrangements. However, heads of government and tourists usually seem to be the only ones to enjoy this type of drumming. Malian women prefer to dance themselves at their own celebrations in the streets instead of cheering »pros on a stage«.

12.-14. Jina is a word borrowed from Arabic and means »spirit« in the languages of Mali. A spirit can be the cause of various mental and physical illnesses, which are treated by female healers. Once a person has regained health after therapy, he or she will be initiated into the healer's cult. During this ritual, the spirit is allowed to take possession of the person, something which will be repeated from then on at many feasts to come. This involves dancing into a trance and on toward the threshold of ecstasy so that the spirit can take possession. In this state, the spirit is given complete theatrical and therapeutic expression. The drummers' role is to call the spirits and make their bodies dance.

See also »The Jenbe Realbook Vol. 1«, a book of music notation closely corresponding to this CD. It contains the complete transcriptions of all its tracks.

Read more about the musicians and music presented here in Rainer Polak’s ethnomusicological study of traditional celebration music in Bamako »Festmusik als Arbeit, Trommeln als Beruf« (Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2004)

The editor

Dr. Rainer Polak studied social anthropology, African liguistics, Bambara language, and History of Africa from 1989 to 1996 at Bayreuth University (Germany), and jenbe music performance from 1991 until today in Bamako (Mali). All of his studies and work in Bamako were accomplished with the help of the outstanding drummers whose playing is presented in this CD. Polak worked as a professional jenbe player in Bamako in 1997/98, performing at well over a hundred weddings, spirit possession dances, and other celebrations, being hired most often by the late Jaraba Jakite, and occasionally by the late Yamadu Dunbia, by Jeli Madi Kuyate, and by Drissa Kone. The ethnomusicological dissertation and book he wrote on that experience won the academic prize of the German African Studies Association in 2003/04. Polak ranks as an outstanding jenbe soloist in Germany. As a teacher he has specialized in giving focussed classes on micro-timing, and master-classes in jenbe solo performance.

Reviews

"It is very clear and clean. One djembe solo and one dunun on each track. The djembe minimalist's dream. This CD has a few tracks by one of the oldest djembe grandmasters alive today. I think he is in his 80's. [note: the recordings are from 1995; jenbe soloists Yamadu Dunbia (1917-2002) and Jaraba Jakite (1953-2005) have passed away in thre meanwhile] When Abdouli Diakite listened to this grandmaster playing he told me, "this man is a master". I have never heard Abdouli say that so clearly about anyone before. Listen closely to his solo style and phrasing. It is the closest you can find to the original sound because he was alive playing djembe before it became popular and was modified by the younger generation. This CD offers a special chance for serious students."

Jeremy Chevrier - www.rootsyrecords.com/HtmlFiles/DjembeCDRecommendations.htm