The Jenbe Realbook Vol. 1 + Vol. 2

The Jenbe Realbook Vol. 2

This music book contains the complete transcriptions of the CD: The Art of Jenbe Drumming: The Mali Tradition Vol. 2 (bibiafrica records 2008)

The tracks

CD Track number. | Title | Playing Time | Page number |

1 | Sanja | 02:37 | 1 |

2 | Sunun | 03:10 | 5 |

3 | Suku (+ Farabaka) | 04:17 | 10 (+ 15) |

4 | Numun-dòn | 02:47 | 20 |

5 | Fura | 02:34 | 25 |

6 | Bòbò-fòli | 01:03 | 28 |

7 | Dansa | 03:44 | 30 |

8 | Bara | 03:37 | 36 |

9 | Sogolo | 02:57 | 41 |

10 | Kirin | 03:15 | 45 |

11 | Jina-fòli | 04:29 | 51 |

12 | Tansole | 03:30 | 57 |

13 | Nyagwan | 03:23 | 63 |

14 | Manjanin | 04:22 | 67 |

15 | Garanke-dòn | 04:09 | 77 |

16 | Sumalen | 01:58 | 85 |

17 | Niare bòn ka lajè | 01:51 | 88 |

18 | Degu-degu | 01:59 | 92 |

The musicians

Jenbe: Jeli Madi Kuyate (Tracks 1 – 3)

Drissa Kone (Tracks 4 – 15)

Jaraba Jakite (Tracks 15 – 18)

Dunun: Madu Jakite (all tracks)

The recordings

Performances in a duo ensemble - one jenbe, one dunun - were typical of the music for celebration style of Bamako in the 1960's and 70's and into the 80's. The studio recordings presented in this CD originated in the years 1995 to 2006. Nowadays larger ensembles are normal. The Bamako style has been influenced by the playing styles of Conakry, Abidjan and also the international jenbe scene in Western countries.

The recordings are an attempt to represent the aesthetic ideals of the classical Bamako duo-style. The jenbe player in a duo ensemble carries a great responsibility: he must continually bring groove and individual expression together. Drumming fireworks and heated ornamental expression is only half of what's required. The repertoire of drumming rhythms, each with a character and design all of its own, are in such a way articulated, that the concentration on the essence of the rhythm is identified, i.e. the fundamental patterns, feelings and phrasing which each rhythm characterises. An art of playing which realises this, is described as "deliberate" or "considered"; literally "composed" (Bamana: "basigilen"). This insistence on the fundamental issues is the speciality that distinguishes the Bamako style.

The transcriptions

In the international scene of West African drumming it has been standard for some decades not to assign notes and rests, but rather to notate the beats in a graphical form. This raster is supposed to denote the so called elementary pulsation, a background and fundamental pulsation of fast and equally-spaced (isochronous) time intervals, which, as the smallest metrical units, define the timing, perception and the ensembles’ synchronisation of the polyrhythms. In concordance with this idea, all the rhythms in this book are notated with reference to a metrical system of 12 or 16 pulses.

The following sound symbols are used in the transcriptions:

| Jenbe |

S | open jenbe slap |

S | closed (or muffled) jenbe slap |

T | open jenbe tone |

T | closed (or muffled) jenbe tone |

B | jenbe bass |

. | jenbe tip (or ghost note) |

| Dunun |

X | closed (or muffled) dunun stroke |

O | open dunun stroke |

While the basic sounds of the jenbe are mostly clearly discernable, there are sometimes differentiations and transitions. For example, the hand is often relatively loose, and sometimes also rounded in the Bamako style of jenbe playing. This makes it sometimes difficult to distinguish between open and closed slaps, or between simply quieter strikes and tips.

Working with these notations

Working with the transcriptions in this book helps familiarisation with the Bamako jenbe music only when it is accompanied by continual reference to the sound recordings. It is only through listening to the recordings that one can gain a conception of the sound that should be produced by playing the notations. It is advisable to listen to the accompanying CD "The Art of Jenbe Drumming - The Mali Tradition Vol. 2" as often as possible.

When practicing with the book, you should listen to the CD at the same time. One good practice method, designed to internalise the sounds, feelings and phrasing, is to listen to the CD and synchronously play the dunun or a jenbe accompaniment pattern. In this way it is possible to imitate the manner of education of jenbe players in Mali, who receive no direct tuition, but rather play accompaniment patterns at celebrations for their master for many years. This type of learning is not the fastest, but certainly the most profound.

Practical tip: for listening to the CD I use closed studio/monitor headphones, with additional professional ear protection under the headphones. The headphones dampen the sound of my own instrument, and give a balanced soundscape. The additional ear protection reduces the higher overall exposure, without overly distorting the complete sound.

The more you have played accompaniment while listening to the CD through headphones, the more it will be worthwhile simultaneously and attentively listening to the solo player and reading the notations. Eventually it will be possible to play the tracks, or parts thereof directly from the notations, either live (in a duo) or synchronously with the CD, or with the dunun pattern as a loop (through the headphones). Admittedly, this will bring more satisfactory results, the more the player has immersed him/her self in the music by following the hearing and accompaniment playing method described above.

It is hopefully self evident that no notation book can replace working with a good teacher. Moreover, it is not possible to get around playing and practicing the material, neither by working solely with such a book, nor by only receiving tuition from a good teacher. When someone wants to master an instrument, or merely play with a basic technical solidity, whether it is the violin or jenbe, piano, trombone or dunun, it requires intensive practice over many years on that instrument. The potential contribution of a book of notations like the Jenbe Realbook is restricted; it can merely help to access the ideals.

Problems with the notation

A reflected approach to notations in the case of jenbe music is especially important. After all, it was until only a few decades ago a matter of the music being passed on purely by listening and repeating. While European notation and music theory has developed together with the occidental music over circa a thousand years, music ethnologists began only in the 1960's to write down and analyse the west African percussion music; i.e. notation of jenbe music began only about 30 years ago. It is not surprising that the notation system of jenbe music is not yet so correct, as it may one day become. I would now like to address two serious problems.

Ambiguities regarding the beat

Most jenbe rhythms reveal a clear beat reference point. Although this can be strongly offset by counterbalances produced by certain accent structures, it will never be completely overridden. Some rhythms however appear to allow two different interpretations. In this group belongs Sanja (also called Jeli-foli or Jeli-don), a rhythm of the Jeli (griots) from Western Mali. The interpretation which I now prefer identifies the beat with those pulses, on which most steps of the dancers, hand claps of the singers and onlookers as well as the starting point of the jenbe solo players patterns fall. Most Europeans however hear the rhythm the other way around, earlier I too heard this rhythm the other way. This alternative perception shifts the beat two pulses backwards; so this beat is positioned for me nowadays in off-beat; its "1" on my "1 and". Both perceptions suggest something out of the ordinary: my current interpretation means that some very common accompaniment patterns appear to be placed in unusual places regarding the beat. The alternative means that the jenbe signal would start on the "4 and" and not on the "1":

1 | . | . | . | 2 | . | . | . | 3 | . | . | . | 4 | . | . | . |

|

| Sanja Beat-Bezug 1 |

O |

| O |

|

| O | O |

| O |

| O |

|

| O | O |

|

|

| kleine Dunun Begleitung (im Quartett) |

T | T | S |

|

| S | S |

| T | T | S |

|

| S | S |

|

|

| Jenbe Begleitung |

O |

| X |

|

|

| O |

| O |

| X |

|

|

| O |

|

|

| Basis-Dunun (im Duo) |

B |

|

|

| S | S |

|

| B |

| T | T | S | S |

|

|

|

| Solo-Jenbe Basis-Pattern 1 |

TT |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

|

|

|

|

| Solo-Jenbe Blocage |

|

| 1 | . | . | . | 2 | . | . | . | 3 | . | . | . | 4 | . | . | . | Sanja Beat-Bezug 2 |

|

| O |

|

| O | O |

| O |

| O |

|

| O | O |

| O |

| kleine Dunun Begleitung (im Quartett) |

|

| S |

|

| S | S |

| T | T | S |

|

| S | S |

| T | T | Jenbe Begleitung |

|

| X |

|

|

| O |

| O |

| X |

|

|

| O |

| O |

| Basis-Dunun (im Duo) |

|

|

|

| S | S |

|

| B |

| T | T | S | S |

|

| B |

| Solo-Jenbe Basis-Pattern 1 |

TT |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

|

|

|

|

| Solo-Jenbe Blocage |

So which of these two views is correct? If anything that is the wrong question. In my opinion the better arguments - dance steps, hand clapping patterns, breaks - speak in favour of the first perception. But the second perception also offers advantages. For example, some jenbe solo players play complex improvisations with triplets, which according to my notation (beat reference 1) start and end in off-beat. According to the second interpretation, these improvised and expressive rhythmical excursions go together with the beat and are therefore easier to play. Examples are to be found in the lines 19,22,29 and 30 of the Bara rhythm, which exactly like Sanja appears to allow two different beats:

1 | . | . | . | 2 | . | . | . | 3 | . | . | . | 4 | . | . | . |

|

| Bara Beat-Bezug 1 |

O |

| O |

| O |

| O |

| O |

| O | O |

| O |

| O |

|

| Dunun Basis (2 Zeilen / Pulse) |

O |

| O |

|

|

| X |

| X |

| X | X |

| X |

| O |

|

|

|

T | T | S |

|

| S | S |

| T | T | S |

|

| S | S |

|

|

| Jenbe Begleitung |

SS |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T | T | S | S |

|

|

|

| Jenbe Blocage |

|

| 1 | . | . | . | 2 | . | . | . | 3 | . | . | . | 4 | . | . | . | Bara Beat-Bezug 2 |

|

| O |

| O |

| O |

| O |

| O | O |

| O |

| O | O |

| Dunun Basis (2 Zeilen / Pulse) |

|

| O |

|

|

| X |

| X |

| X | X |

| X |

| O | O |

|

|

|

| S |

|

| S | S |

| T | T | S |

|

| S | S |

| T | T | Jenbe Begleitung |

|

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T |

| T | T | S | S |

|

| SS |

| Basis-Dunun (im Duo) |

It appears to me that for the jenbe and dunun players in Mali the pattern |TTS..SS.| in the rhythms Sanja and Bara are actually the same as |S..SS.TT| in Dansa or Tansole. For these musicians one pattern does not change into another because of a different beat reference. The relationship to the other parts of the ensemble is first and foremost the determining factor, particularly the main pattern of the dunun. The perception by Europeans is in contrast heavily driven by a linear measure. In our perception a changed beat reference can cause a quasi turnaround of the pattern, which can in turn take on a completely different figure.

If we want to get closer to jenbe music and its corresponding musical concepts, we have to try and disassociate ourselves from our excessive dependence on a linear metric system. Alternative beat references for a rhythm should not in this sense be understood as competitive, and ultimately pretentious demands on the rights of interpretation. They can also coexist. Thus it is a good exercise to learn rhythms such as Sanja and Bara twofold, i.e. to hear and play the same patterns in two different beat relationships, and then to change the beat while playing, to learn quasi to switch. Admittedly this is not an end in itself, but rather serves, by practice, to loosen oneself from the beat. The goal is to play figures in relation to other figures. Furthermore, the abovementioned and widely popular jenbe accompaniment pattern doesn't really meet very well either the notation |TTS..SS.| or |S..SS.TT|. It is better described as |SS.TTS..| : the player starts as a rule with the two slaps. When verbalised the figure is also begun with the two slaps ("gapang kidipang" or similar). The longer two pulse rest delimits the pattern, afterwards the next unit begins. The two tones are neither the start nor the prelude, they are in the middle of the pattern. A one dimensional beat driven orientation is if anything impedimental to the path towards a pattern orientated conception. The deciding factor is the practice of the perception of the pattern, and this is most successful when one plays the solo jenbe solely with the dunun (in duo or through headphones). It is advisable when practicing to dispense where possible with a metronome or beat orientated accompaniment parts, except for new patterns which are not yet stable.

Feeling

The elemantary pulsation of most jenbe rhythms from Mali does not consist of a string of pulses which have a consistently even spacing. Rather the sub-division of the beats is structured by 3 or 4 faster irregular pulses: the single pulses have different lengths. The long and short pulses generate regular patterns, and repeat themselves after every beat. This patterns remains stable during the course of most tracks. We can describe them as "metrical feelings". Each of these feelings creates a certain swing. The Bamako jenbe music knows at least four such feelings. There is for example the ternary feeling of the type "short-medium-long-short-medium-long-...", to which many important rhythms from the region Manden belong, for example Suku and Manjanin. Numun-don is also among this type. Then there is a second ternary feeling with the model "long-short-short-long-short-short-...". This feeling forms the basis of some known rhythms from the Wasulun region, eg. Kirin but also others such as Sumalen and Bòbò-fòli. A number of rhythms with the feeling "long-short-short-..." contain the option of an additional pulse, which subdivides the first long pulse in two shorter ones. This additional pulse appears not only selectively, for example as an ornament (flam/roll), but also in basic patterns like echauffements and signals. When the motional pattern of the jenbe player is considered, it becomes obvious that we're looking at a pulsation of four. Essentially, the rhythms with the feeling of "long-short-short-..." have more similarities with quarternary rhythms than they do with the ternary rhythms of the "short-medium-long-..." feeling.

The binary "long-short-long-short-..." feeling is known through various styles of Jazz and other Afro-American dance styles. It appears in the Bamako jenbe music in the rhythms Sanja, Fura und Dansa. It is possible, just as in the Shuffle feeling, to perceive these rhythms as ternary, especially in a slower tempo, or at least to intersperse some solo patterns as ternary, like in Bara.

Lastly there is the quarternary feeling "short–medium–long–medium–short–medium–long–medium–…", marked by, amongst others, the rhythms Jina, Sunun and Sogolo.

These feelings appear to have been overlooked in the mediation and appropriation of jenbe music in Europe and America, although Johannes Beer in his accompanying text to Famoudou Konates CD "Rhythmen der Malinke" - a milestone of the global jenbe movement - clearly referred to them and presented the first analysis and interpretations thereof. There exists now a backlog. In our modern society the task of music theory, notation and pedagogy is to assist the understanding, playing and passing on of the integral structures of music forms. Metric feelings are among these underlying structures of jenbe music and other dance music forms. Theory, notation and instruction should adapt to the music forms, not vice versa. According to this, music theory, notation and instruction must be so composed, as to promote an understanding and conveyance of these feelings. This has not been accomplished until now. These shortcomings are also apparent in the notation at hand, in that the feelings are not taken into consideration. The same shortcoming, incidentally, applies to the notation of the ornamental compaction - double hits (flams) and roll combinations: they are set in a linear, even raster, although in reality they constitute organically formed patterns.

The notation used here comes across as crude and rigid as against the above all organic patterns and feelings of jenbe rhythms. I hope nevertheless, that this publication represents not only two steps sidewards, but also one step forwards. A backlog exists ultimately not only in the metric fundamentals of jenbe music, in its Gestalt-orientation and feelings, but rather also in the area of its musical form. The strength of this book of notations lies in the fact that it makes complete tracks readable. It is possible, by reading along, to develop a sense for the changes and sequences of the fundamental patterns and improvised insertions, with which the jenbe players, without set arrangements, design both cyclic and progressive form schemes and, ultimately, spontaneous performance-compositions of musical pieces. During this process I wish all readers much enjoyment and success.

I would like to thank Thomas Bauer-Haberbosch, who entered the notes into the computer, the publisher Dieter Weberpals, and Sean Mahoney who translated the above introductory remarks into English language. And I raise my hat once again to Jeli Madi Kuyate, Drissa Kone, Jaraba Jakite, Madu Jakite und Yamadu Dunbia, these splendid musicians from Bamako, who play so well, that the arduous task of transcribing was not only instructional, but also fun.

Bayreuth, Sommer 2008 | Rainer Polak |

The author

Dr. Rainer Polak studied social anthropology, African linguistics (including the Bambara language, the lingua franca of Mali), and history of Africa from 1989 until 1996 at Bayreuth University. Since 1991 he has learnt, practiced and researched the jenbe music of southern Mali. Polak worked as a professional jenbe player at celebrations in Bamako for one year in 1997/98, performing at over a hundred weddings, spirit possession dances and other celebrations. He played mostly for Jaraba Jakite, but also Yamadu Dunbia, Jeli Madi Kuyate and Drissa Kone. The ethnological dissertation he wrote based on that experience won the academic prize of the German African Studies Association in 2003/04. In 2006/07 he led a musicological research project on the timing of jenbe rhythms at the Bayreuth University. Polak ranks as one of the outstanding jenbe solo players in Germany. As a teacher he concentrates on the further musical education of jenbe teachers.

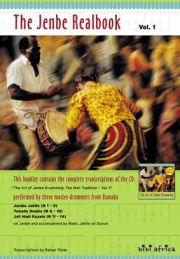

This book contains the complete transcriptions of the CD:

»The Art of Jenbe Drumming: The Mali Tradition Vol. 1«

The CD was recorded 1995 in Bamako by Rainer Polak, first released with Bandaloop Records in 1996 and re-released with bibiafrica records in 2006 (www.bibiafrica-records.de)

The transcription follows the order of the CD tracks

1 Intro + Fula 04:25, 2 Madan 06:25, 3 Maraka 04:44, 4 Sogoninkun 04.43, 5 Sabaro 04:55, 6 Woloso 04:20, 7 Kòmò 06:50, 8 Kòfili 05:37, 9 Kirin 05:12, 10 Burun 03:48, 11 Maa Nyuman 01:44, 12 Jina I 04:18, 13 Jina I 02:52, 14 Jina III 02:41

The music was performed by

Jenbe: Jaraba Jakite (Tracks # 1 – 5), Yamadu Dunbia (Tracks # 6 – 10), Jeli Madi Kuyate (Tracks # 11 – 14), Dunun: Madu Jakite (all tracks)

The recordings

In the recordings, three masters of traditional jenbe dance drumming present the clear beauty and explosive power of their music. Of course the music of a jenbe dance celebration cannot be adequately documented because it represents part of a dynamic event which can only be fully grasped by witnessing all its interlocking elements. The sound recording of a celebration would lack the movement of the dancers and the whole atmosphere of colors, smells, and enthusiasm. The recordings presented in this CD, moreover, were made not in the context of a celebration at all, but in a school yard in the Badialan quarter of Bamako. The drummers performed for the microphone, without rehearsals, without arrangements, and without an underlying notion on how to convey celebration music without a celebration. It was the first time to do a studio recording for all of them. They spontaneously created a kind of »art music« in a space without references, an abstract translation of music traditionally played for celebrations. The original live tracks were neither cut, nor overdubbed.

The ensemble

The CD presents masters of the jenbe in duet performances with an accompanying bass drummer – one jenbe, one dunun, no bells. Playing in this smallest version of a jenbe drum ensemble was typical for the celebration music style of Bamako in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Today, trio, quartett, and even larger ensembles are the rule, and many stylistic influences from ballet music, the playing styles of Conakry and Abidjan, and of the international jenbe scene based in the rich West, have come to change the Bamako style. Thus the recordings featured here represent sort of a classical aesthetic ideal of Malian jenbe music as crystallized in its capital Bamako after independence.

Only mature musicians can master duet playing and know how to create its typical fascinating musical density, balancing the tension between flow and transition, between communal groove and individual expressivity, between tradition and improvisation, between form and trance. The »challenge of the void« that duet playing presents to many holds no threat for the drummers of Baladian, because their playing is based on decades of experience as performers in this sort of ensemble. Fabulously sure of their instruments, guided by close communication even in the boldest passages, the void represents space they enjoy to fill with sound.

The reduced line-up also has the advantage of very clear and transparent sonic reproduction. Thus the listener can not only perceive the fundamental musical structures, but also experience the high art of drumming, the »talking of the drum«, in its finest rhythmical nuances and timbral shades.

The transcriptions

As has become usual since the 1960s in studies of West African percussion music, the notes are set in relation to a graphic raster that represents a linear metric system of elementary pulses (smallest time units except of rolls/flams) and beats (comprising either 3 or 4 pulses to larger units). Thus all rhythms transcribed refer to either a quaternary metric system of 16 pulse cycles (4 beats x 4 pulses) or to ternary 12 pulse cycles (4 beats x 3 pulses).

The following sound symbols are used in the transcriptions:

S jenbe slap

S closed or muffled jenbe slap

T jenbe tone

B jenbe bass

X closed or muted dunun stroke

O open dunun stroke

Without doubt, the transcription published here do not make an exception from the rule that a musical transcription can always be only an imprecise and incomplete approach to represent a sonic reality. Working with the book makes sense only if the reading of the music comes along with hearing the CD. Hearing the CD, plus of course hearing other jenbe music, continuous practicing basic skills like sounds etc, and studying with a good teacher, are much more important than working with the book, and are preconditions to being able to successfully work with the book.

Let me hint at some of the most important aspects of the music that are not adequately represented in the notation. While the basic sounds of the jenbe (bass, tone, slap) are pretty clearly discernable most of the time, they are not transcribed in their further differentiations or fluid transitions. For instance, sometimes bass tones are played so softly that you can also interpret them as “ghost notes” or “tips”. Slaps as played by Dunbia and particularly by Kuyate are often almost, yet not completely closed, making it difficult to make a clear-cut distinction between open and closed slaps. While these “dirty” sound characteristics are typical for the duet playing style of Bamako, and important to the musical result, they are very hard to transcribe. This is the case even more so with the phrasing of the rhythmic patterns. Malian jenbe playing, and duet performance in particular, literally lives by metric feelings that make the rhythm swing. If you measure in milliseconds the densificating ornaments performed by the three jenbe soloists, you will find that most of them do neither go conform with any linear derivation of the basic pulsation (double-time, sextoles, or the like), nor correspond to what is termed a “flam”. They are usually “broader” than a flam, and are unevenly structured: they represent patterned microrhythmic structures – the setting of which in the framework of a metric raster of elementary pulses is unjust and arbitrary. Even the basic pulsation itself frequently is not evenly spaced, as supposed by a linear metric understanding and notational system, but compressed and stretched alternately, in ways that produce rhythmic swing. This feeling can be applied to such an extent that the distinction between binary (or quaternary) and ternary rhythms begin to dissolve. For instance, while the dunun pattern of rhythm Burun is ternary, Yamadu Dunbia consistently phrases many of his jenbe patterns in a way that is very much in between a ternary (XxxXxx) and quaternary (X.xxX.xx) feeling. This is not due to ideosyncratic personal style or weird improvisations, it rather is inherent in the composition of the rhythm and its basic patterns. When measured, one even finds that the actual phrasing sometimes is closer to a quaternary pulsation (four pulses per beat) than to the dunun’s ternary feeling. Or listen to Jina 1, where many an allegedly quaternary pattern turns out to feel like being ternary. Structures of micro-timing is about the hardest thing to transcribe I can imagine, yet so essential to the music in question that this difficulty really means deficiency. At the moment I have the privilege to do more research on the timing of jenbe rhythms with the generous help a the German Research Council (DFG). I hope that this research will allow me also to think over the assumptions and delimitations of raster notation, and accordingly try to develop its capability to consider micro-rhythmic phenomina.

Bayreuth, spring 2006 Rainer Polak

The author

Dr. Rainer Polak studied social anthropology, African liguistics, Bambara language, and History of Africa from 1989 to 1996 at Bayreuth University (Germany), and jenbe music performance from 1991 until today in Bamako (Mali). All of his studies and work in Bamako were accomplished with the help of the musically outstanding, yet rather locally and traditionally minded drummers whose playing is presented in this book and the corresponding CD. Polak has worked as a professional jenbe player in Bamako for one year in 1997/98, performing at well over a hundred traditional weddings, spirit possession dances and other celebrations on the basis of being hired by the late Jaraba Jakite, most of the times, and occasionally by the late Yamadu Dunbia, by Jeli Madi Kuyate, and by Drissa Kone. The ethnomusicological dissertation and book he wrote on that experience won the academic prize of the German African Studies Association in 2003/04. Polak ranks as an outstanding jenbe soloist in Germany. As a teacher he has specialized in giving focussed classes on micro-timing, and master-classes in jenbe solo performance.